The legacy of an historian of enslavement

Published: November 2023

Betty Wood (1945-2021) was a Girton Fellow almost all her career.1 The only female lecturer in the Cambridge History Faculty when she was appointed in 1974, later a Reader in American History, she was as committed to her subject as she was inspiring in the teaching of it. Generations of undergraduates and her many graduate students found her guidance hugely engaging and supportive.

Her own doctoral years, at the end of the 1960s, had taken her overseas to the University of Pennsylvania, where she saw the aftermath of the civil rights movement at first hand; she became an historian of African Americans. Alongside broad ruminations on the origins of American slavery, her primary focus was on the plantation colony of Georgia. Slavery in Colonial Georgia, 1730-1775 (1984); Women’s Work, Men’s Work: The Informal Slave Economies of Lowcountry Georgia (1995); Gender, Race, and Rank in a Revolutionary Age: The Georgia Lowcountry, 1750-1820 (2000): it is in her Georgian books that we find resonances to Girton College’s much more recent enquiries.

Photograph of Betty Wood (detail) taken by Prof Simon Szreter, 2017 (archive reference: 6/2/162/4).

On the Importance of Context

Taking it as crucial to conceiving a history of enslaved populations, these works lay stress on examining the precise social context -- geographical, temporal, political, cultural -- of each one. While true of any social historical study, Wood’s work offers a masterclass in mining such contextual framings for details of her subjects’ daily life, and for the lived experience of people who were actively and deliberately barred from themselves marking the historical record in conventional ways. Because the worlds of enslaved persons were kept restrictively small, exactly where they lived was the greatest determinant of health, material possessions, language, religion, family experience and community life. This was the emphasis of Girton Reflects no.4, which describes the locales of plantations we now know to be connected to Girton. These included the Florida frontier, as enslavers forward-settled the then-territory until the American Civil War; the broader geographic region of the Caribbean, whose islands were largely held together through shared farming practices and ideologies; and rural Virginia, which of the three most resembled Georgia.

Putting historical narratives about enslaved populations into their contexts also places them as contemporary actors in those times and spaces. Approaching materials that the Working Group had acquired from this perspective enabled it to see, for instance, the impact of armed conflict on enslaved communities. Thus, the War of 1812, between Britain and the young United States, disrupted the supply of provisions, as well as livestock movement and seed imports, all of which affected the working patterns of the approximately 35 people known to us as living on one of Virginia’s plantations along the Appomattox River.

Likewise, during the First and Second Seminole Wars,2 enslaved groups on the Florida frontier built makeshift ramparts and generally supported militias manned by their enslavers. In Slavery in Colonial Georgia, Wood discusses the implications of a volatile political climate and of emerging questioning within settler society concerning the morality or legality of enslavement and the application of slave-codes to the Black population. Some of this is also germane to what we have learnt of the impact of pronatalist ideology on family life and of contemporary debates about the conditions of enslavement in Demerara and the West Indies.

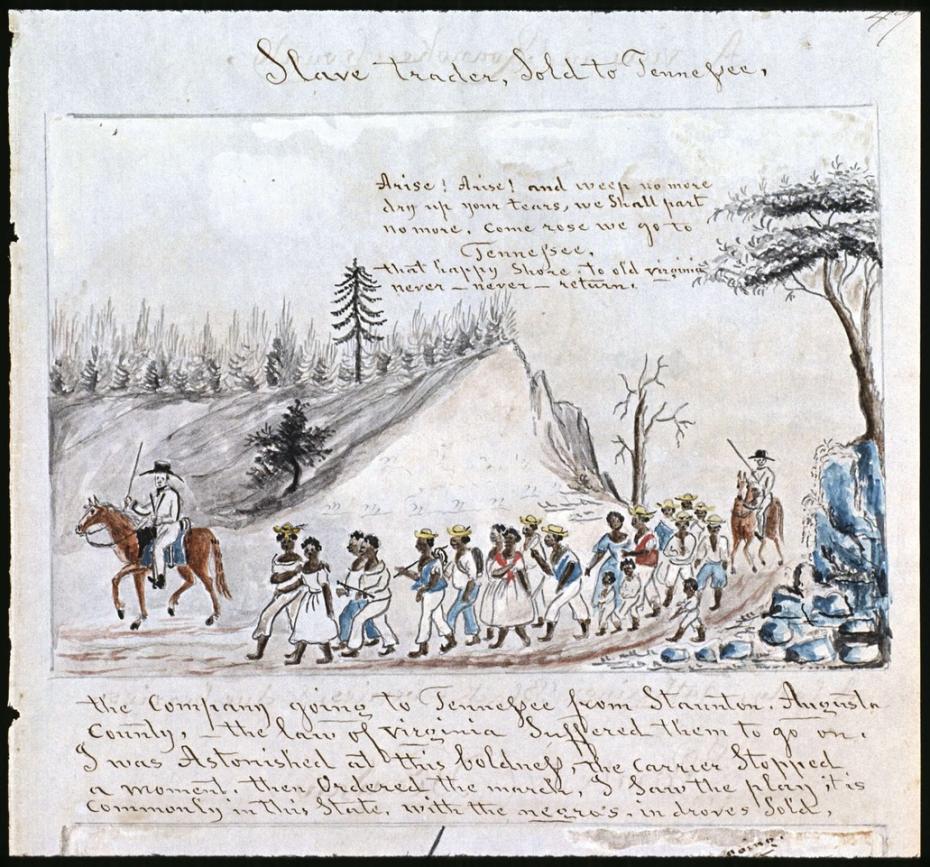

Geographic context informed many other aspects of the life of enslaved people. What were the implications of running away from a frontier plantation when it was hundreds of miles from the nearest town? Or of a location having a robust local press that would emphasize rewards for runaways and publish accounts of how enslavers punished their malcontents? The very kinds of ‘markets’ and means of ‘sale’ to which enslaved persons were subjected had significant effects on their expectations.

‘Slave Trader, Sold to Tennessee’, from Sketchbook of Landscapes in the State of Virginia by Lewis Miller, Virginia, circa 1853. Image held by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, USA.

Daily Life and Personal Experiences

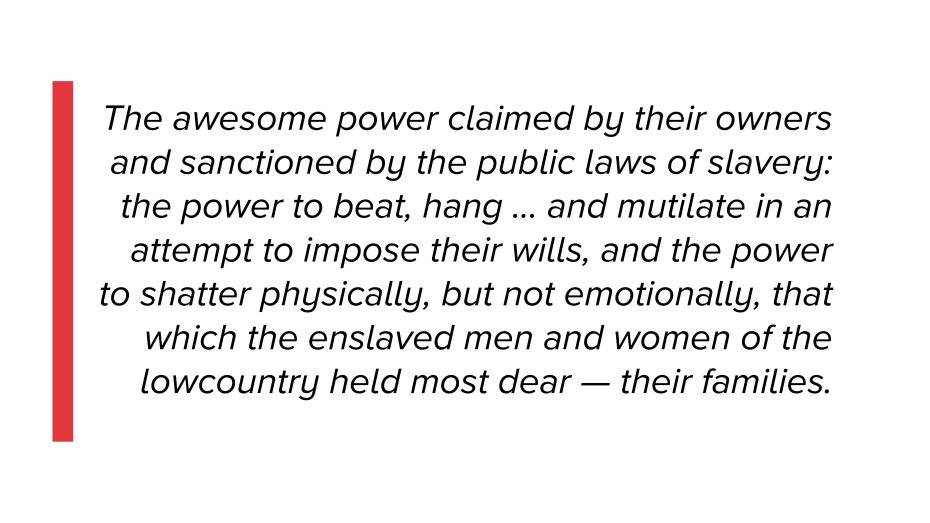

In her extended case-study of the Georgia Lowcountry, Wood consistently focuses on what can be known of Black people, and of the enslaved rather than their enslavers. She was concerned to explore the dynamics of power — what she described as ‘bondpeople’s continuing struggle to secure and retain recognized rights as producers and consumers’ that took place within ‘the context of what may be termed the formal slave economy’. 3 In this way, Wood identified ‘remorseless struggles’ and ongoing negotiations with -- and rebellion from -- the slave-owners’ awesome power.

Betty Wood, Women’s Work, Men’s Work: the Informal Slave Economies of Lowcountry Georgia, (Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 1995), p. 3.

The passage highlights two additional characteristics of Wood’s work, both of which have been influential in the historiography of enslavement. Firstly, it shows her uncompromising approach to the horrors of enslavement. Unlike many of her academic predecessors, Wood refrains from euphemisms. Instead, she lets the records speak for themselves, replete as they are with violence, murder and sexual assault. Also notable, secondly, is her engagement with the history of emotions, which was then in its infancy as a field of historical research.

In exploring the motivations, relationships, behaviour and emotional responses of enslaved persons, Wood gives Girton’s LE enquiries a framework for contextualizing some of the accounts and case-studies being brought to light. An example is the way in which she frames various forms of economic sabotage on the part of enslaved persons. These included running away, feigning illnesses and thieving, actions that Wood sees as potent tools of self-protection, family preservation and weapons of negotiation. This has aided us in scrutinizing and characterizing similar episodes as they arise in our primary source materials.

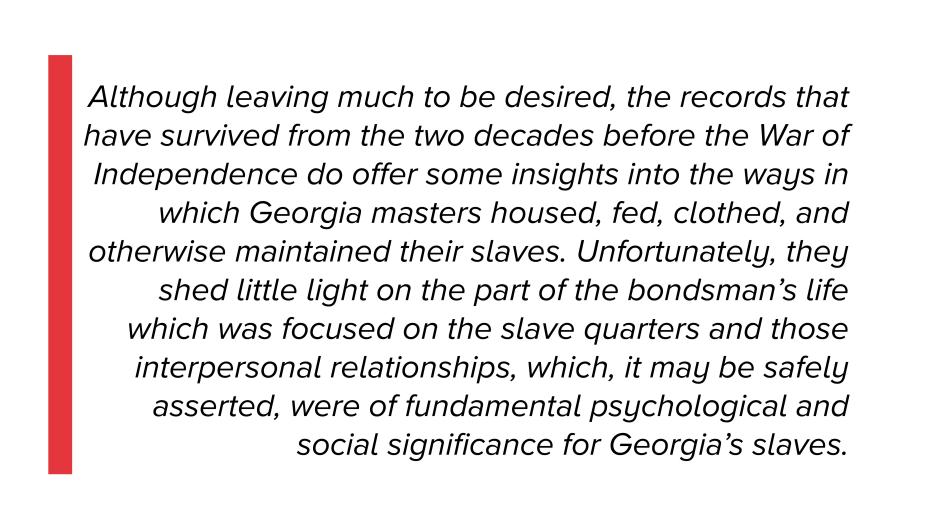

Methodological insight gained from Wood’s scholarship also comes from the categories of analysis she used in composing accounts of everyday lives. Thus, she recovers details from descriptions of agricultural processes for growing this or that crop or for raising certain livestock; from lists of skilled labourers and what their arts/crafts/skills might entail; from the logistics of tools used, sermons shared with enslaved groups, orders of foodstuffs; from dress patterns, and other documents and commentaries, drawing such information into categories for understanding. In addition to effectively demonstrating how to maximize source materials such as plantation ledgers, schemes for crop rotations, garden plans and sundry orders, Wood’s work shows us how to use them to construct narratives. It has been helpful to divide the information about plantation communities gathered by the Working Group into analytical categories such as food, clothing, health, religion, labour. Slavery in Colonial Georgia differentiates between people’s public and private lives, separating their work regimes, activities and comportment into what was done in front of and for the benefit of white society from what was done for self, family, and (their own) community.

On Women and Children

Betty Wood was one of the first historians to look specifically at the gendered experiences of enslaved populations. Women’s Work, Men’s Work makes a particular space for women’s lives, a subject of interest throughout her career.

![Waud, A. R. (1867) Rice culture on the Ogeechee, near Savannah, Georgia / sketched by A.R. Waud. Savannah Georgia, 1867. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/93510740/.](/sites/default/files/styles/930_scale/public/images/master-pnp-cph-3b30000-3b39000-3b39700-3b39730u.jpeg?itok=rju1gc37)

Waud, A. R. (1867) Rice culture on the Ogeechee, near Savannah, Georgia / sketched by A.R. Waud. Savannah Georgia, 1867. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/93510740/.

An important difference between men and women among the enslaved in the American South lay in the inherent sexual and reproductive connotations of buying and selling where the latter were involved, since the value of enslaved women was tied to their age and reproductive health. This added layers of fear and anguish for women subjected to chattel enslavement. Wood also examines the role of childbirth, child rearing and childhood on plantations in Georgia. If we think of Wood’s use of indirect pointers, so far we have only come across a few oblique references to children from our primary sources: an estate manager’s ledgers from Virginia make us aware of six children through an order for enough cloth to make them clothing; one letter recommends that, to keep them out of mischief, enslaved children under the age of six be given piglets to raise.

In emphasizing the role of family in enslaved communities, Wood shows it as simultaneously a refuge and a source of joy and comfort under harsh conditions. However, family was also the foundation of one of the greatest cruelties of enslavement. The potential for family separation and/or the anguish of seeing kin harmed or sold is central to the understanding Wood puts forward about the emotional lives of enslaved people. This is something played out several times in materials from Virginia, and will be taken up in the next Girton Reflects.

Identifying Gaps

Consider a letter written on Christmas Day 1815 by the same manager in Virginia to the plantation’s absentee owners, Mr and Mrs Dunlop, who lived in London. The manager reported that he had distributed various items of clothing sent from the Dunlops to the ‘deserving’ among the enslaved population (whom he refers to collectively as ‘the People’). He then added, ‘I have remembered Mrs Dunlop to all of them & they seemed proud to think that she had not forgot them’. 4 He goes on to tell the Dunlops about the yearly ledgers, inventories, and the raising of the plantation’s hogs.

The LE Committee is continuing the Working Group’s investment in bringing to light as many names and individual stories as can be gleaned from the historical record in connection with Girton’s legacy. One is reminded of an enduring question about institutional and historical records: who is being remembered across distance, across time? There is also something to be said about who gets to be remembered as an individual in historical narratives: those entitled to specifics, to personalized attributes, to their own names – or, if they were the names they went by or simply had imposed upon them, about what their name left out. This is something that Betty Wood stressed was crucial to her work on enslavement in colonial Georgia.

As is shown throughout her written work, a commitment to highlighting individual experiences and relationships, recovering names and personal stories where possible, also meant continually identifying gaps in the archival and historical record, and articulating how these gaps affected any endeavour to detect lacunas in the corresponding historiography.

Betty Wood, Slavery in Colonial Georgia 1730-1775, (Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 1984), p.154.

Legacies and Institutional Memory Work

A sociolinguistic study of how people create life stories touches on institutional memory-building. Institutions ‘work the past, re-presenting it each time in new but related ways for a particular purpose … to create a particular desired present and future’.5 Narration emerges as an important way in which institutions construct who they are, for ‘narrative works to establish identity . . . Narrative is also the link between the way an institution represents its past, and the ways its members use, alter, or contest that past, in order to understand the institution as a whole as well as their own place within or apart from that institution’.6 In so many ways, our LE narratives build on foundations laid down by pioneers such as Betty Wood. At the same time, we are engaged in re-reading, shifting and expanding Girton’s institutional memory and self-knowledge.

Reflection

If we feel grateful to a plantation manager for those occasions when he wrote down the names of individuals, that written legacy is also a legacy of colonial control through systematic record-keeping, by and large a closed book to the names’ bearers. But what might he have said of the gaps he was conscious of? And how might the ones he didn’t bring to mind have nonetheless spoken to Girton’s LE inquiries? Betty Wood passed away during the very year that the LE Working Group was getting its research off the ground. We find we have been re-tracing many of her own footsteps, some advisedly, some inadvertently no doubt. Hers was a legacy that moves us to ask such questions.

Written by Legacies of Enslavement Committee (dated: November 2023)

Coming Next: No. 8, January 2024

Presences and absences: Roslin, Virginia

Documents from the plantation that helped form Gamble’s wealth give a tantalizing glimpse of some of the individuals enslaved there and the relationships they cherished.

Citations:

- See Alastair Reid’s obituary of Betty Wood in The Year: The annual review of Girton College, Cambridge, for 2021/22, pp.124-26, on which this sketch draws. A symposium honouring Wood’s work in the context of Girton’s Legacies of Enslavement enquiries was held in College on 4 November 2023, and the substance of what follows comes from the address given by Maggan Kalenak, Researcher to the LE Committee.

- 1817-18 and 1835-42; the wars were named after Indigenous residents of the land being opened up for settlement.

- Wood, Women’s Work, Men’s Work, p. 2.

- Letter from William McKean to James Dunlop, 25 December 1815, The Roslin Estate Papers, Library of Virginia, Accession 23873 (Part 2).

- Linde, Working the Past, p. 14.

- Linde, Working the Past, p. 4.

References:

- Linde, Charlotte, 2009. Working the Past: Narrative and Institutional Memory, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wood, Betty, 1984. Slavery in Colonial Georgia 1730-1775, Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press.

- Wood, Betty, 1995. Women’s Work, Men’s Work: The Informal Slave Economies of Lowcountry Georgia, Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press.