A Spectrum of Connections

Published: June 2023

Girton owed its foundation and its rapid growth to the gifts of many individuals – women and men – who gave sums of money large and small to the new College. In Britain in the 1860s and 70s, opening and sustaining a residential college where women could study and be examined to degree level was a radical project. One of the greatest obstacles to success was money: how could such an initiative be funded?

Ventures of this kind attracted less financial support than their male equivalent. The plan was for annual self-sufficiency through fees once enrolments increased. But what would support a building; or the early costs of a small establishment; or growth? What of scholarships for worthy students from less affluent families? No public funds were available. Some charitable institutions gave important donations, but the bulk of the money that allowed the College to open and then expand came from private individuals.

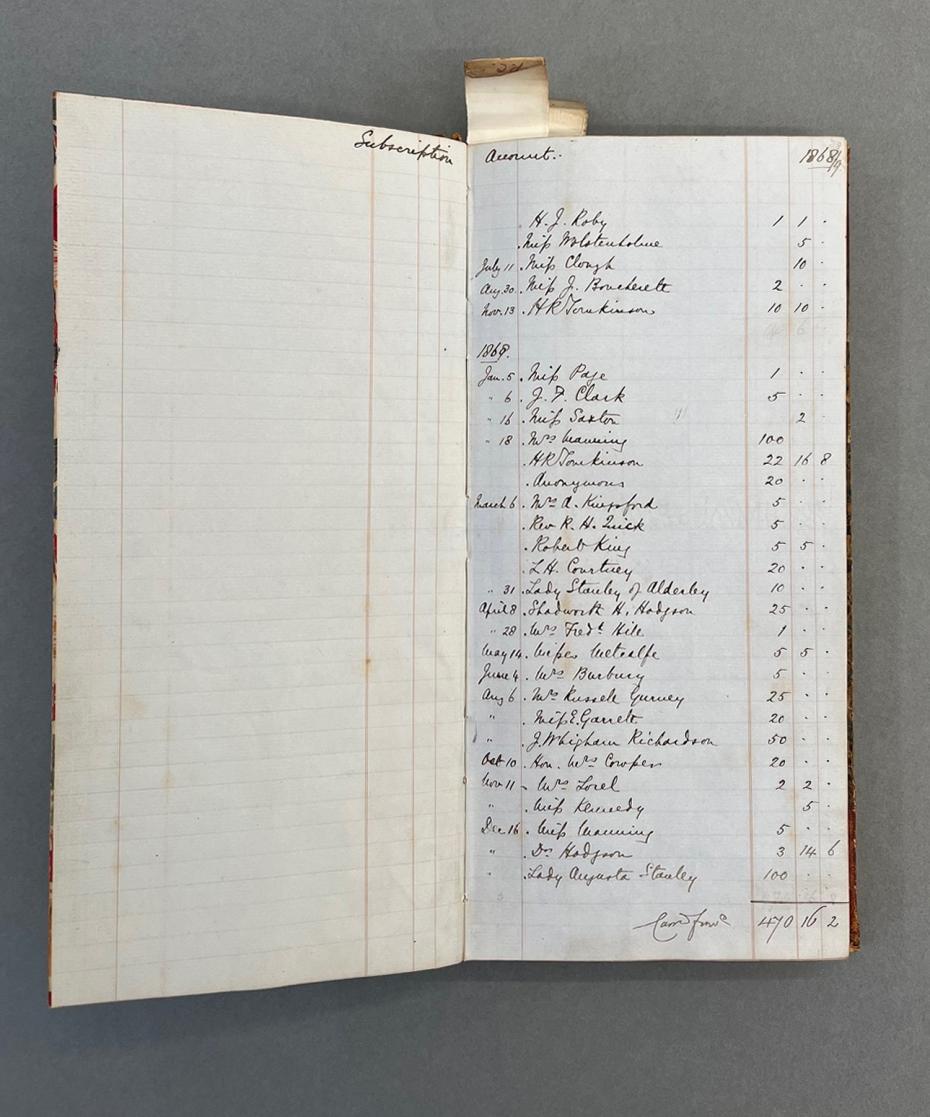

Part of a hand-written list of subscribers, 1868–1869 (archive reference: GCAR 4/1/2pt). This early list was compiled by Emily Davies.

Our research has underlined how much the College owes to early, diverse forms of individual giving. By 1900, there were a small number of donations of £2,000 and above, a significant number of between £100 and £2,000, but several hundred smaller gifts of anything from 5 shillings to £99.00. Some can be investigated; the great majority are very hard to trace. Modest donations and public anonymity may reflect middling or small incomes, hence perhaps a decreased likelihood of wealth linked to enslavement. But this is usually impossible to confirm.

More sizeable gifts or a higher public profile offer more scope for research. Jane Catherine Gamble, the largest individual donor up to 1900, is the subject of an earlier piece in this series. We also considered the circumstances of five other women: Emily Davies, Barbara Bodichon, and Henrietta, Lady Stanley of Alderley, together with Girton students and Staff members Katherine Jex-Blake and Gwendolen Crewdson. Did any have family connections to the Atlantic trade in enslaved people, or to profits made through enslaved labour?

![Part of a list of financial contributions, from the College [Annual] Report, 1898 (archive reference: GCCP 1/1/1pt).](/sites/default/files/styles/930_scale/public/images/GCCP1-1-1AnnualReport1898-ContributionsP53-54-colour300dpiweb.jpg?itok=RRUb83R-)

Part of a list of financial contributions, from the College [Annual] Report, 1898 (archive reference: GCCP 1/1/1pt).

It quickly became apparent that it is impossible to draw a binary distinction between those families ‘connected’ and those ‘unconnected’ to enslavement. The far-reaching penetration of eighteenth and nineteenth-century British society by the profits of enslavement make it difficult to conclude that even moderately wealthy families were completely unconnected over two or three generations to plantation and other enslaved production. The problem only grows with greater wealth. In place of this binary model, the concept of a ‘spectrum of connections’ is far more revealing, extending from ‘highly connected’ to the profits of enslavement at one end, to ‘likely to be essentially unconnected’ at the other. But even then, unqualified assertions are rarely possible.

Emily Davies

Of the five, Emily Davies (1830–1921) came from the most economically modest background. Research found no evidence of family connections to wealth generated by enslavement. Emily actively supported abolitionism, and it can be argued that experiences in that campaign were one factor leading her to the cause of improving the condition of women. This will be the subject of a later piece in this series.

But some questions remain. Emily’s father, John Davies, was an Anglican clergyman, dependent on his clerical stipends. His estate, possibly with additional support from Emily’s brother, another clergyman, was sufficient to allow his adult daughter and widow to live in modest comfort in London after his death. Historians now know more about the complex connections between the historic wealth of the Anglican church, and profits from enslavement. Is this a factor to bear in mind? Emily’s maternal grandfather was a manufacturer of Fuller’s earth. We know little more. Fuller’s earth had many uses in the nineteenth century, including in scouring textiles. It is possible this economic activity was given a boost by the import of cheap raw materials produced by enslaved workers, or by exports to the southern United States. We do not know.

Images: (left) Emily Davies by Rudolf Lehmann, 1880, cropped (archive reference: GCPH 11/33/53). (right) Photograph of Lady Stanley, taken by S Kohn, Hof-photograph of Karlsbad, circa 1870, cropped (archive reference: GCPH 4/1/2).

Henrietta, Lady Stanley of Alderley

Research concerning Henrietta, Lady Stanley of Alderley (1807–1895) has also found no direct evidence of a connection between her, her husband, their parents or grandparents, and wealth generated through enslavement. It is also notable that Henrietta’s father, father-in-law, and husband were all outspoken advocates of the abolition of enslavement, and her close political partnership with her husband, Edward, Baron Stanley of Alderley, suggests Lady Stanley would have supported him in these views.

However, there is some shade to the picture. Henrietta’s correspondence reveals that throughout her marriage she and her husband mixed with people from a wide spread of backgrounds and with diverse opinions on the matter of enslavement. They welcomed leading abolitionists into their home, but also mixed on occasion with known enslavers. Indeed, there was a kinship connection to enslavement through one of Henrietta’s brothers, who married into a family with complex links to plantation production, and who expressed some associated ideas in his letters. There is no evidence that Lady Stanley shared his opinions, and some that she did not.

![Henrietta Jex-Blake (standing); Violet Buxton, née Jex-Blake, Adela Kensington and Katharine Jex-Blake (seated, l-r), taken by J[?] Hartmann of Bayreuth, 1889 (archive reference: GCPH 5/8/4). Violet and Henrietta were two of Katharine’s eight sisters. Adela Kensington, later Mrs Adam, was a student at Girton 1885–89, (when she would have been taught by Katharine), later a Staff Lecturer in Classics, and a Cassel Research Fellow.](/sites/default/files/styles/930_scale/public/images/GCPH5-8-4VioletJBAdelaKennsingtonKatherineJBAndStandingHenriettaJB1889sepia300dpi-crop.jpg?itok=qux48f9_)

Henrietta Jex-Blake (standing); Violet Buxton, née Jex-Blake, Adela Kensington and Katharine Jex-Blake (seated, L-R), taken by J Hartmann of Bayreuth, 1889, cropped (archive reference: GCPH 5/8/4). Violet and Henrietta were two of Katharine’s eight sisters. Adela Kensington, later Mrs Adam, was a student at Girton 1885–89, (when she would have been taught by Katharine), later a Staff Lecturer in Classics, and a Cassel Research Fellow.

Katharine Jex-Blake

Katharine Jex-Blake (1860–1951) was the daughter of a wealthy, land-owning, and office-holding Norfolk family. Her father, Thomas Jex-Blake, was an Anglican clergyman, school headmaster, and latterly Dean of Wells Cathedral. In 1879, eighteen-year-old Katharine joined Girton in its 11th intake to read Classics. After four years as a student, and one as a schoolteacher, she returned to College in 1885 to begin 37 years on the resident staff, the last six as Mistress.

The Jex-Blake household was scholarly and academic, valuing education for its daughters as well as its sons. Katharine’s aunt, Sophia Jex-Blake, was one of the first British women to qualify as a doctor (in Switzerland); her sister Henrietta became a Principal of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

On neither side of Katharine’s family has evidence has been found of any connection to enslavement, back to both sets of grandparents. That said, as with Emily Davies, the issue of historic connections between the wealth of the Anglican church and profits from enslavement might once again require consideration. In addition, Katharine’s maternal grandfather, John Cordery, was a prosperous merchant in tea: some evidence suggests possible connections to the East India Company, which profited from the traffic of enslaved people in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. However, although currently it cannot be ruled out that Katharine’s maternal family drew income from trading structures which had benefitted from enslavement, no clear evidence has so far been found that they did.

Photograph of Barbara Bodichon, taken by Disdéri of Paris, circa 1870, cropped (archive reference: GCPH 4/2/2).

Barbara Bodichon

Turning to Barbara Bodichon (1827–1891), we find that the complexity grows. Barbara’s paternal grandfather, William Smith, was a prominent abolitionist who worked closely with William Wilberforce for the abolition of slavery in the British colonies; her beloved aunt, Julia Smith, was directly involved in the campaign to abolish enslavement in the West Indies; and the household of her father, Benjamin Smith, frequently enjoyed visits from leading anti-slavery activists.

As a young woman, Barbara followed this family tradition and became an active abolitionist. She married in 1857. Eugene Bodichon had been a leading supporter of the 1848 abolition of enslavement in Algiers, then a French colony. The couple spent several months in 1857–1858 travelling in the United States, including many weeks in the southern states. Her letters and journal from that time (published in 1972 as An American Diary, 1857–58), roundly criticised slavery, and forcefully condemned the conditions and experiences of the many enslaved people she encountered.

Two other factors can be weighed. The first is sizeable: the Smith family wealth, which in time would give Barbara the income and independence to make her substantial contributions to Girton, was first established by her paternal great-grandfather, Samuel Smith, through the import and sale of sugar, and via connections to plantations in the Caribbean and the southern United States. In this way, the initial Smith family wealth was to a considerable extent built by the labour of enslaved workers. Subsequent generations of the family abhorred and worked to end enslavement, and they actively diversified the family’s enterprises. But this longer history is material to the wealth which allowed Barbara’s gifts to Girton.

A further complex point concerns the letters and journal of 1857–58. Barbara’s condemnation of enslavement as a huge injustice is clear. She described it as a perverting and degrading institution that harmed the entire society, and both condemned and occasionally challenging men and women who defended it. Her account is intersected with frequent depictions of the brutality inflicted on Black individuals, including children; she visited auctions of the enslaved, roundly decrying the treatment of individuals as cattle to be inspected and sold; she also visited Black churches, presenting them as a source of comfort and support for their congregations. But despite this genuine and detailed criticism, to the modern eye some of Barbara’s vocabulary can seem naïve and patronising, exoticizing those whom she describes – as in the way she sometimes sees them as an object of study, or of a potential painting. On occasion her prose reveals some of the painful assumptions about race and the racialised thinking of her age. At the same time, her efforts to engage with Black families and communities in their own spaces would have set her apart from many other travellers and commentators.

Gwendolen Bevan Crewdson, aged around 17, taken by Lafosse of Knolls House, Manchester, circa 1889, cropped (archive reference: GCPH 6/2/11/3). Gwendolen spent her childhood in Manchester.

Gwendolen Crewdson

Gwendolen Crewdson (1872–1913) joined Girton in 1894 to read Natural Sciences; from 1900–1905 she took up a series of staff posts, culminating in three years as Junior Bursar, supporting her modest salary by family means. She made several small monetary and other gifts to the College and purchased and eventually bequeathed ‘Crewdson’s Field’ to Girton.

Consider the details. Both Gwendolen’s parents had died before she was 9 years old, and she was raised by her brother, a lawyer. Her father and paternal grandfather, however, had been wealthy Manchester-based merchants and manufacturers of cotton and cotton goods, immediately raising the question of profits from enslaved labour. Her mother was a Waterhouse, the sister of Girton’s first architect. That family had historic plantation interests in the British colonies in Guyana and the Caribbean, and in the import and trade of goods produced using enslaved labour such as cotton, tobacco, coffee, and spices – Gwendolen’s great-grandfather, Liverpool-based Nicholas Waterhouse, had first created the Waterhouse wealth through these imports and via outward trade to the Caribbean.

Closer scrutiny produces additional information. It transpires that Gwendolen’s father and Crewdson grandfather were very active anti-slavery campaigners, where feasible promoting and selling cotton produced through ‘free labour’. On the Waterhouse side, there is evidence that as a young man, Gwendolen’s maternal grandfather, Alfred Waterhouse Snr, began distancing himself and his investments from connections to enslavement. By the time Gwendolen benefitted from her family’s wealth, the documented links to enslavement were probably two generations in the past. However, it cannot be ruled out that profits from enslaved production had passed down the generations, feeding into that wealth and into Gwendolen’s philanthropy, including her gifts to Girton.

Reflection

Five studies; five complex pictures.

The complexities here relate to the fortunes and views of individuals. The background that helped make their lives and their gifts to Girton possible only shows through from time to time. What historians now know about the economics of enslavement and about the unforeseen consequences of abolitionism are not in view. Here we stay with our five notable women. If one were indeed to draw up a spectrum in terms of their ‘connections’, including their apparent commitment to or aversion from the principles of enslavement, where would one place each of them? And what would one be weighing up?

Across each of these accounts, we are reminded that by the middle and later decades of the nineteenth century little British family wealth was entirely unconnected from the profits of enslavement. Our new and more detailed knowledge adds to our history, and to our fuller understanding of the debt owed to the previously unseen, the previously unrecognised.

Written by Legacies of Enslavement Committee (dated: June 2023)

Coming next: No.4, July 2023

Plantation Life in the 19th Century

What the Committee has learned of the daily life of the enslaved on the kinds of plantations now part of Girton's history.