An intriguing image

A group portrait, a religious conference, and the encounter between a Black American preacher and one of Girton’s early supporters

How did a pioneering Black preacher from an enslaved family come to be memorialized together with one of Girton’s early supporters? What do their overlapping histories reveal of the complex times in which each lived? They might be in the same painting but is there any common ground between them?

Published: September 2023

The painting

Each summer between 1874 and 1888, a gathering of clergy and lay-people took place at Broadlands, the country home of the wealthy William and Georgina Cowper-Temple. The ‘Broadlands Conferences on the Higher Life’ attracted men and women interested in contemporary Christian evangelicalism, spiritualism and debates about the idea of Christian holiness. Among the participants was the artist Edward Clifford who, around 1887, completed a large painting inspired by one particular conference.

Edward Clifford (1844–1907), A group portrait of the Broadlands Conference, painted circa 1887. Girton College is grateful to John McNeil for permission to reproduce this image.

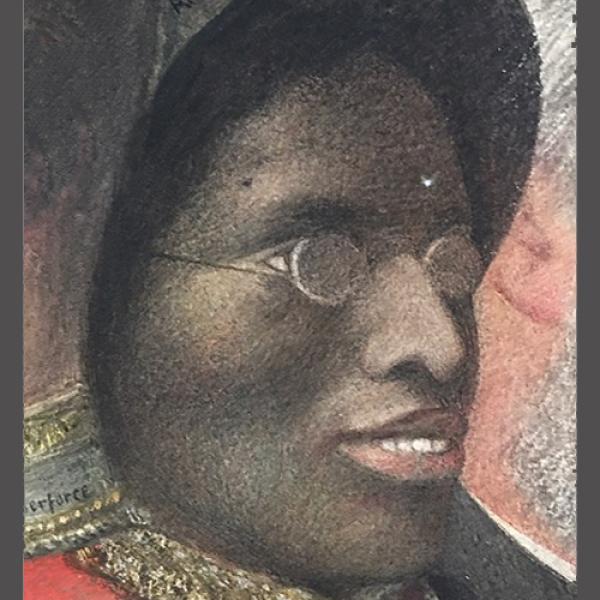

This dramatic group portrait consists of more than 40 individual representations of people at the Conference of 1879. Among those given prominence in the small group to the right is a woman significant to Girton: Emelia Russell Gurney. Her posture, expression and dress imply seriousness and focus, as does her placing in relation to the central figure. To the left, in the middle of a larger group of smaller figures, almost hidden behind a military uniform, we glimpse a face in profile, that of Amanda Berry Smith, a visiting preacher and evangelist from the United States. Amanda’s features are less clear, but hers is a notable presence in a group like this.

Two women

Emelia Russell Gurney

Emelia Gurney (1823-1896) has already figured in our series (see Girton Reflects no. 5).

Engraving based on a circa 1866 portrait of Emelia Russell Gurney by George Frederic Watts, engraving created by Frederick Hollyer, and found in the frontispiece of Letters of Emelia Russell Gurney, edited by her niece, Ellen Mary Gurney, originally published 1902, University of California Libraries reprint.

In 1852, Emelia Batten, daughter of a clergyman schoolmaster, married the wealthy barrister and subsequent MP, Russell Gurney, becoming known as Mrs Russell Gurney. The couple had no children. Emelia’s life history demonstrates the importance of mid-nineteenth-century philanthropy to the success of institutions such as Girton. It also illustrates how many members of Britain’s elite in this period were connected in sometimes contradictory ways to the consequences of enslavement and Empire.

Three elements of Emelia’s life deserve mention. First, her deep Christian faith. Through her mother, Caroline Venn, Emilia had near relatives closely associated with Anglican evangelicalism, and the pursuit of personal religious renewal and social engagement. This included support for Abolitionism – Venn clergymen were key members of the Clapham Sect, which played an important role in the promulgation of the Slave Trade Act (1807) and the Slavery Abolition Act (1833). No proven personal connections to wealth derived from enslavement have yet been found (although a ‘John Venn’ was a clergyman and enslaver in Jamaica in the eighteenth century), but the numerous clerics in Emelia’s genealogy raise the question of historical links between the Anglican Church and profits of enslavement discussed earlier in this series. Emelia’s faith led her to new religious teachings, evangelicalism, even mysticism. A friend wrote of how she loved to sit at the feet of religious and artistic teachers. This and her personal friendship with Georgina Cowper-Temple, who shared many of her religious sympathies, help explain her participation in the Broadlands Conference.

The second element concerns Emelia’s engagement in campaigns led by her friend Emily Davies for improvement in the education of women and girls. Mrs Russell Gurney was among the 13 names on Emily’s 1867 list of proposed members of her first ‘College Committee’, and Emelia quickly hosted meetings where Emily could meet other wealthy women whose financial assistance might be won (a donation came from Georgina Cowper-Temple). More committee memberships followed, and in 1872 Emelia joined the first Governing Body and the Executive Committee.

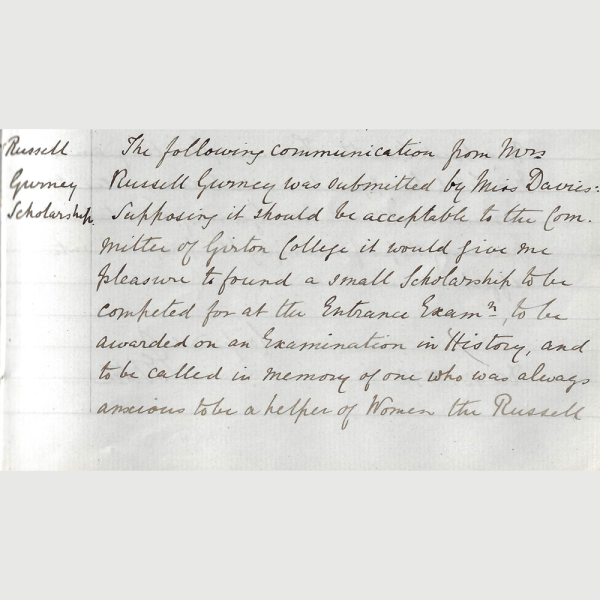

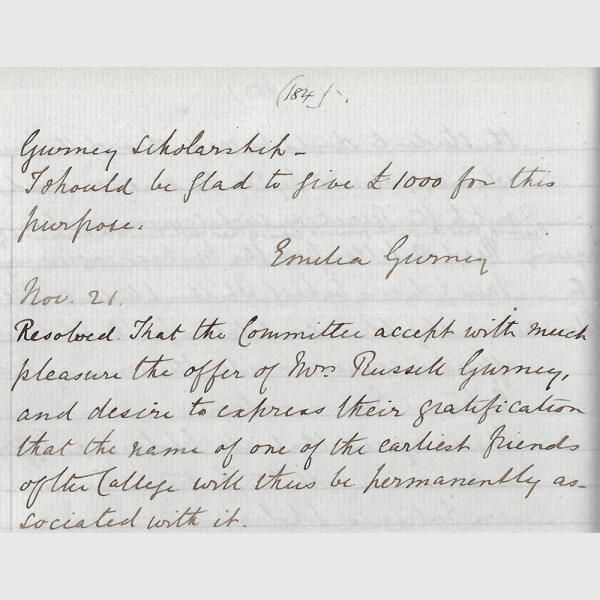

Excerpt from Girton Executive Committee minutes of 25 November 1878, noting the proposed gift from Mrs Russell Gurney of £1,000 to found a scholarship in history (archive reference: GCGB 2/1/5pt).

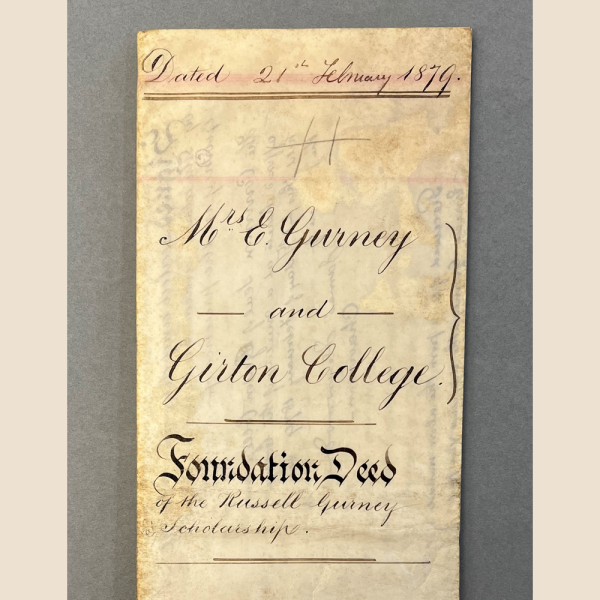

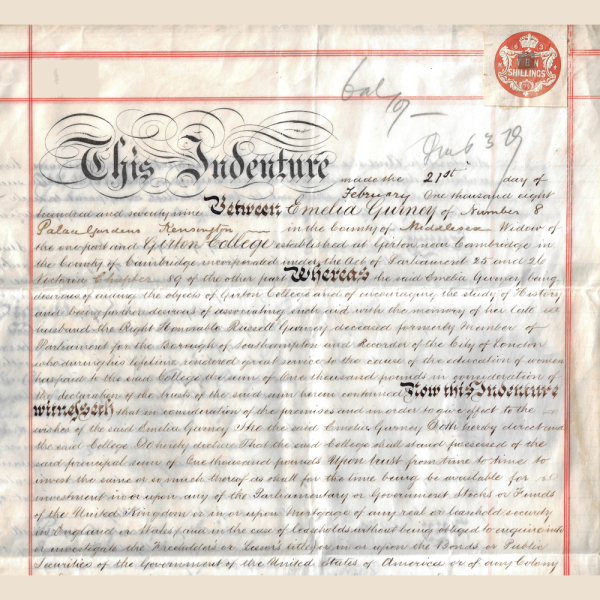

The front and first page of the foundation deed of the Russell Gurney Scholarship, drawn up between Emelia Gurney of 8 Buckingham Palace Gardens, widow, and Girton College, 1879 (archive reference: GCAR 2/6/36/24apt).

The Gurneys were substantial donors to the young college. Gifts from Emelia totalled close to £1,400 and Russell helped underwrite the loan of 1872 required to build on the Girton site. As a widow, in 1879 Emelia gifted a major scholarship in History named after him. She also sent to the new buildings at Girton ‘ten large trees, such that may be sat under … [each] summer’.

Third, Emilia’s visit to Jamaica in 1866. This followed Russell Gurney’s appointment as a member of the Royal Jamaica Commission, which spent three months on the island investigating the Morant Bay rebellion of 1865, and its harsh suppression by Governor Eyre. This Commission has a complex history and legacy. For many recent scholars, the Commissioners’ report insufficiently explored the long-term causes of post-emancipation Black Jamaican immiseration, and its conclusions helped bring about the strengthening and greater centralization of Empire, rather than amelioration of Black grievances. Emelia’s journal and letters from her time in Jamaica, although on the surface open-minded, reveal an outlook marked by contemporary assumptions about race and racial characteristics now abhorred. She gave loyal support to the Commission’s conclusions.

Amanda Berry Smith

In many ways the life of Amanda Smith (1837-1915) is in stark contrast to that of Emelia Gurney.

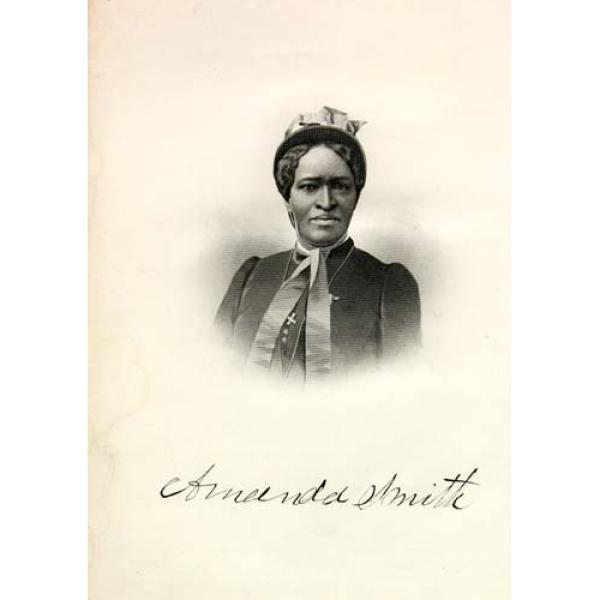

Amanda Berry Smith by T B Latchmore, circa 1885, original photograph held by the United States National Portrait Gallery.

Amanda Smith was born to enslaved parents in Long Green, Maryland. By taking on extra work for money, her father, Samuel Berry, was able to purchase first his own freedom and then that of his family. Amanda had an unusual childhood in one respect. Both her parents had taught themselves to read and write and encouraged their children to learn as well. Amanda attended school, although only for only three months – a few weeks when she was eight at local classes run by the daughter of a Methodist minister; a further short period aged 13, when she walked two and half miles each way to a school where a few Black students were taught after the other pupils’ lessons were over. It was at 13 that Amanda began employment in domestic service in Pennsylvania, and subsequently became a cook and washerwoman. Two marriages ended with her husbands’ deaths (including in the civil war).

Already drawn to intense prayer and worship, during her second marriage Amanda had a profound personal experience of conversion. After being widowed again, through immense hard work and determination, and in the face of considerable opposition, she succeeded in becoming a widely respected preacher and holiness evangelist. First in the Weslyan Holiness movement and African Methodist Episcopal Church, and then internationally, she was to acquire a reputation as a great missionary speaker and worship leader.

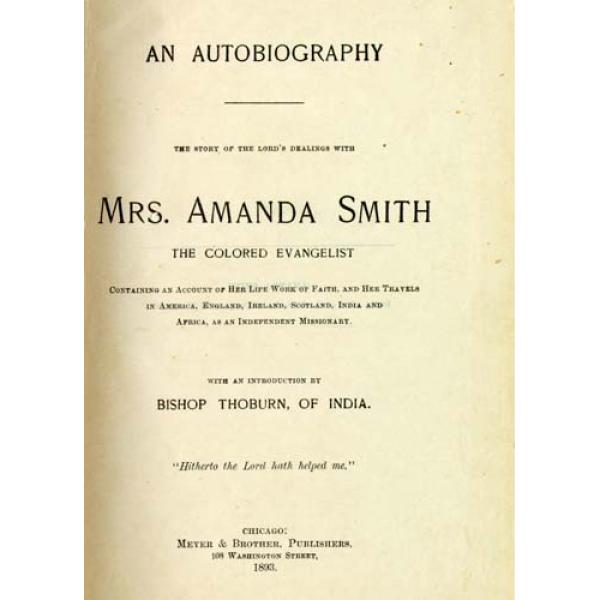

Front pages from Amanda Smith’s Autobiography, showing how she presented herself as an evangelist.

In 1878 Amanda travelled to England for what turned out to be two years, during which she continued preaching (including in Cambridge), followed by several years in India and West Africa, where she preached widely and also worked alongside missionaries. She only returned to the USA in 1890. One of her ensuing educational triumphs was the orphanage for Black children that she founded in Illinois, later named as the ‘Amanda Smith Industrial School for Girls’; Amanda’s name thus came to grace a girls’ educational institution. More widely, she was involved with the temperance movement, and in the 1890s with the ‘Coloured Women’s Clubs’ which took a central role in local social and educational initiatives to support Black communities.

These achievements suggest an independence of mind on the part of someone who had had little formal education herself; we know that she felt supported in her endeavours by her faith. In her autobiography1, she observed of an incident at the 1879 conference, ‘Oh, how He blest me, and, I believe, made me a blessing to the people’.

The Broadlands Context2

The Higher Life movement in England emerged in the 1870s, influenced by the American Holiness Movement. The aim was to help advance a Christian’s progressive sanctification, that is, personal holiness and spiritual growth. — It was just such a sanctification to which Amanda Smith testified in 1868. -- Though principally Evangelical, the movement was non-denominational, and brought together a network of artists, politicians, preachers, writers and reformers, all of whom saw their Christianity as a call to radical transformation, both of themselves and of society.

It is important to contextualize the term ‘evangelical’ here. Whereas in recent years, especially in the United States, evangelicalism has been associated with a private individualized Christianity, this was not true of evangelicalism in the nineteenth century. Rather, the movement, both in the United States and in Britain, was strongly involved in campaigning against the slave trade and other forms of oppression, driven by the explicit conviction that all people, regardless of race, class or creed, are infinitely precious in the sight of God.

It is not surprising that Clifford, an honorary secretary of the Anglican evangelical Church Army, who memorialized the 1879 Broadlands Conference, was also a supporter, indeed someone who had encouraged Amanda to come. Though associated with the Aesthetic movement of the late nineteenth century, the painter was also a campaigning activist and came from a family committed in the ethos of the time to improving the lives and working conditions of the poor and outcast (he worked for the amelioration of those with leprosy).

The Conference of 1879 also included Evan Hopkins, among the founders of the present-day evangelical Keswick Convention, which Amanda had attended; Hannah Pearsall Smith, the inspirational Quaker; F.W.H. Myers, poet and founder of Psychical Research at Cambridge, and the novelist George MacDonald. It was through the George MacDonald Literary Society that a member of Girton’s Legacies of Enslavement Working Group, as it was then beginning to piece together the complex connections between the founding of the College, abolitionist campaigns, enslavement and plantation wealth, became aware of this extraordinary group portrait.

Encounter

Amanda Smith and Emelia Gurney are in the same painting largely because of the specific theological precepts to which they both subscribed. But in what sense do they ‘meet’ each other?

Sections of ‘The Broadlands Conference’ by Edward Clifford, showing (L-R) Amanda Berry Smith and Emelia Russell Gurney. Girton College is grateful to John McNeil for permission to reproduce these images.

Attested both by her appearance in the midst of the others in the group portrait and by contemporary accounts, in personal terms it would seem that Amanda Smith was not demeaned, patronized or treated as a trophy, but rather treated (we might say) with honour and respect as an equal and a fellow speaker.

Amanda’s own description of her visit to Britain reveals a public account, at least, of having met only ‘the utmost Christian cordiality’, where ‘neither ‘colour nor sex was a hindrance’3. It was said of her at the conference, 'She kept up the fire, and the hallowed influence was so great, that one appeared to feel like Paul, "whether in the body, or out of the body, I cannot tell”'4. The incident that called forth her sense of at once blessing and being blessed (see above) was when she was escorted into dinner on the arm of Lord Mount Temple. As she recounts it, she seems to have been charmed rather than over-awed by the luxurious surroundings and her host’s courtesy.

We have no record of what the formerly enslaved child thought of the descendant of Abolitionists, but Emelia has left us a short, vibrant description of encountering the American preacher, who ‘stirred all hearts by … [her] impassioned search for God’5. Emelia was much taken with the preacher’s vehemence and sincerity, and was touched by what she saw as the simplicity of profound faith.

Starting from contrasting conditions of possibility, not least in terms of physical resources, both Amanda and Emilia were moved -- in the idiom of the day -- to improve the spiritual and material lives of others. What is arresting is the role that education for women played in their aspirations.

Reflection

The group portrait gives us no more than a glimpse of Amanda Smith, but it is a glimpse of the wider world of which the ten-year-old Girton College was also part. Who knows if, in the year she funded Girton’s first ever foundation scholarship, Emilia saw Amanda as an educationalist too. But she would have seen a fellow activist. They moved in circles that combined giving voice to the liberation of the oppressed with deep personal spirituality. Perhaps it is for today’s Girtonians to imagine how to translate into present concerns the unknown conversations between these two and the spheres of life they represent.

Coming next:

This concludes the present series of Girton Reflects.

A second series will be launched next academic year (2023-24), on a bi-monthly basis, starting in November 2023.

Citations:

- Amanda Smith, An Autobiography: The Story of the Lord’s Dealings with Mrs. Amanda Smith the Colored Evangelist (Chicago: Meyer & Bro, 1893; reprint [Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers series]: Oxford: O.U.P., 1988).

- With gratitude to the Rev. Dr John McNeil for his assistance and support, and for sharing his expert knowledge of the background to the Broadlands painting.

- Amanda Smith, Autobiography, p.261.

- Letter from George J. Montieth, BR 50/41, 15 August 1879. Broadlands Records, University of Southampton Special Collections.

- Letters of Emelia Russell Gurney, edited by her niece, Ellen Mary Gurney, originally published 1902, University of California Libraries reprint .