Introduction and Welcome

The Mistress introduces the ceremony, reflecting on the generosity of spirit and scale of philanthropy that has built and sustained the College over the past 150 years. Girton started as a dream, a wild flight of imagination, a daring tilt toward the outrageous idea that women should have the same entitlements as men. Buying into that dream brought Girton to life, and as we enter our 151st year of operation during Black History Month, we look to the prolific American poet Langston Hughes to remind us how important it is to have a dream.

Dreams by Langston Hughes (1901-1967), read by the Mistress

The Choir: Let All the World, set by Greta Tomlins (1912-1972)

First Reading, read by George Cowperthwaite, MCR President

Extract On the Progress of Electricity from an interview conducted with inventor Thomas Edison (1847-1931), in 1869, the year Girton College was founded.

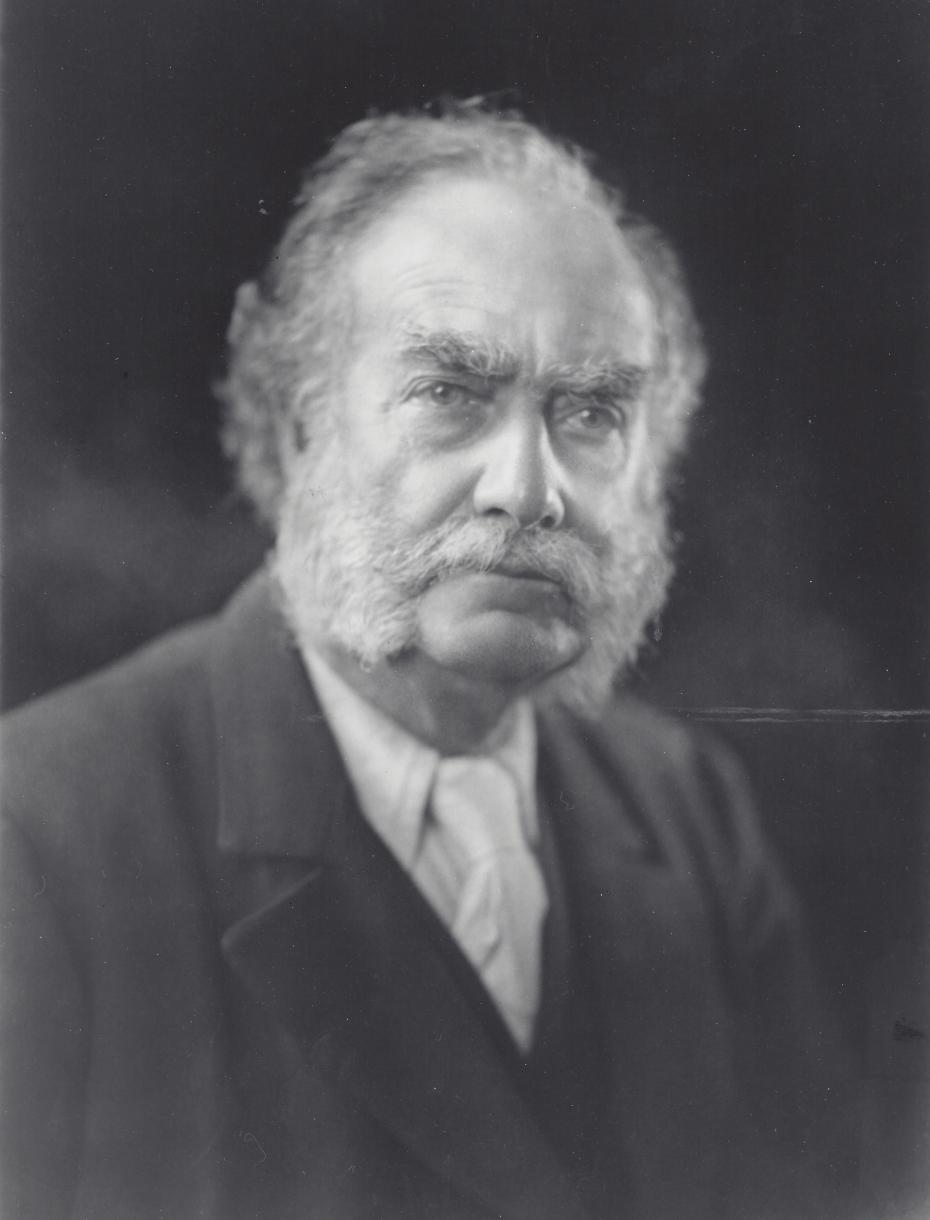

Reflection on the Life and Legacy of Alfred Yarrow

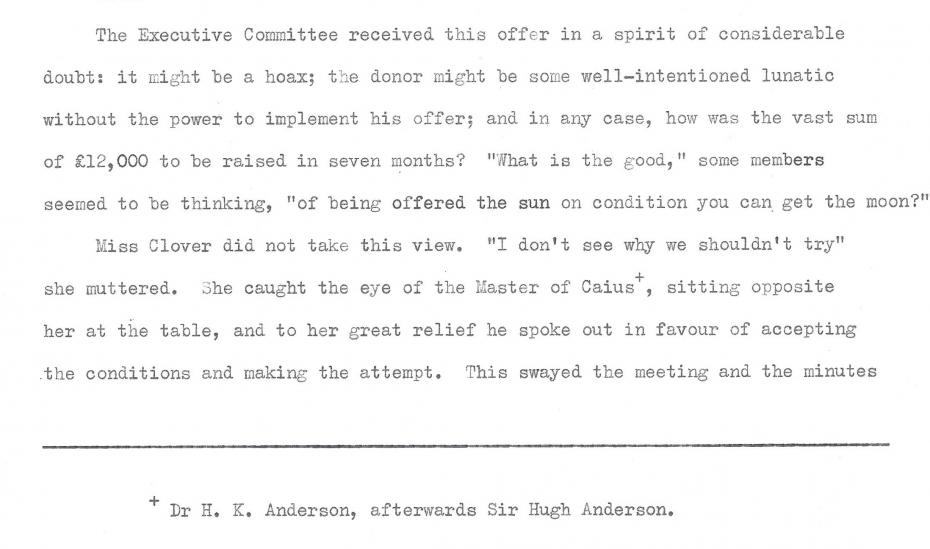

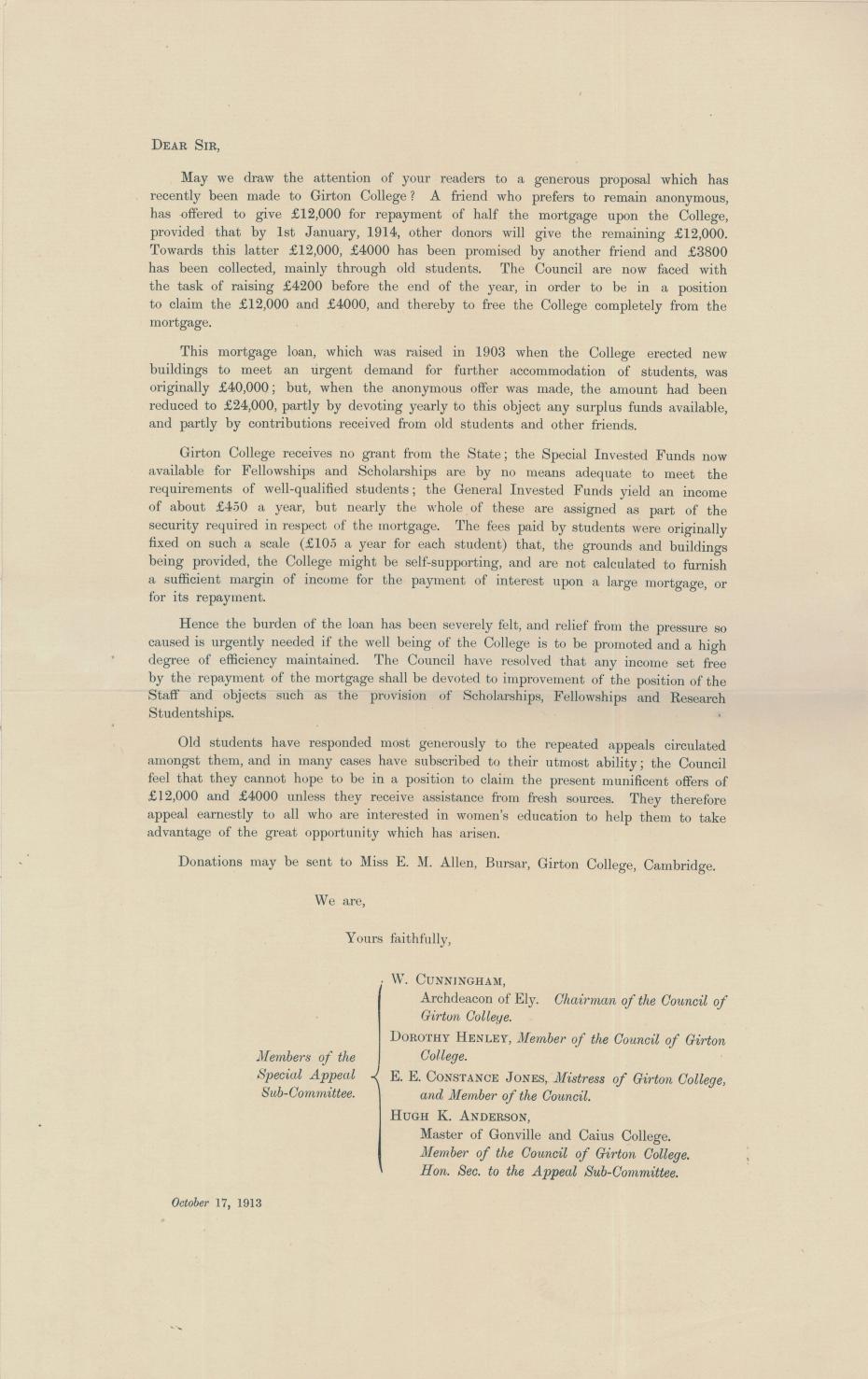

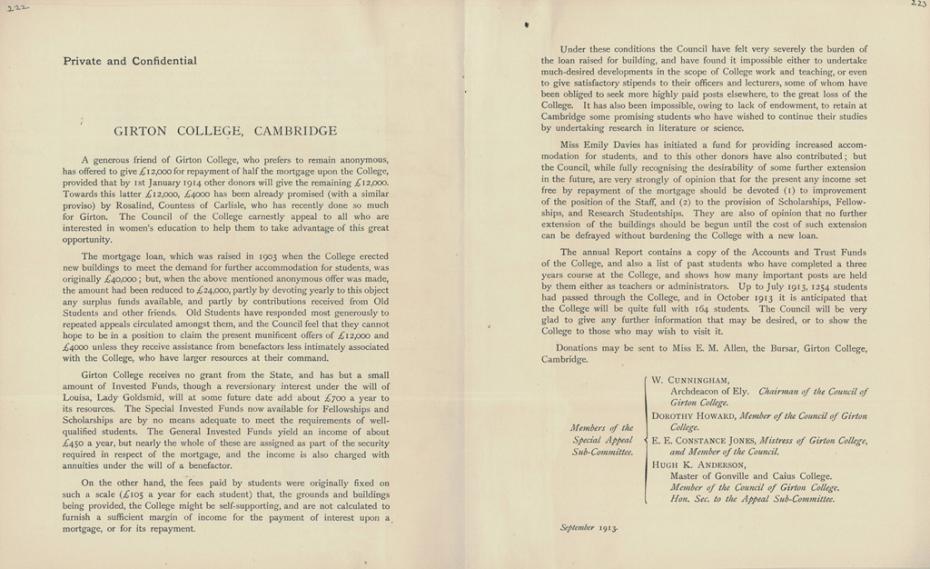

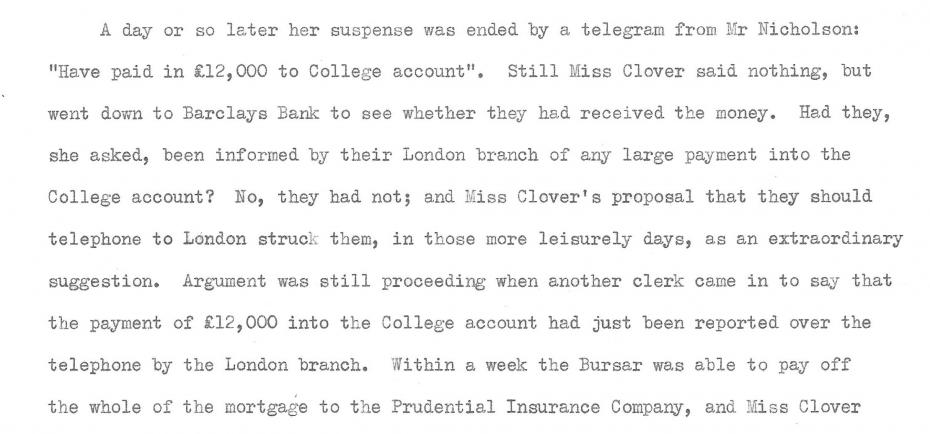

Each year the ceremony for the Commemoration of Benefactors turns our attention to a single key figure, to remind us of the wide range of lively personalities whose gifts over the years have transformed the fortunes of the College. Over the last decade, we have profiled 10 inspiring women including our founders Emily Davies and Barbara Bodichon and ranging across the years to Joanna Dannatt who died only a decade ago. View the complete set of tributes (PDF).

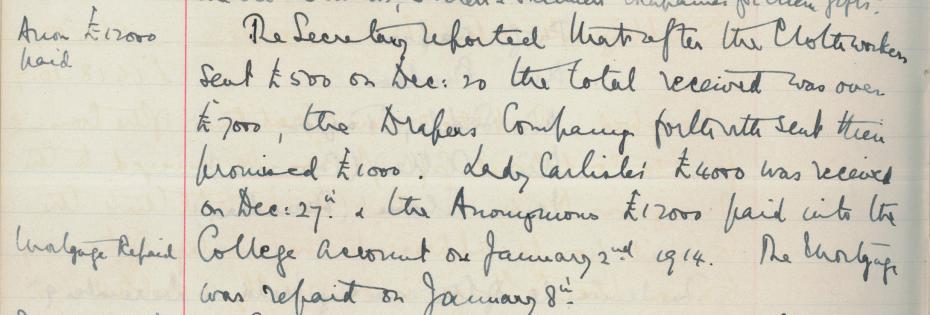

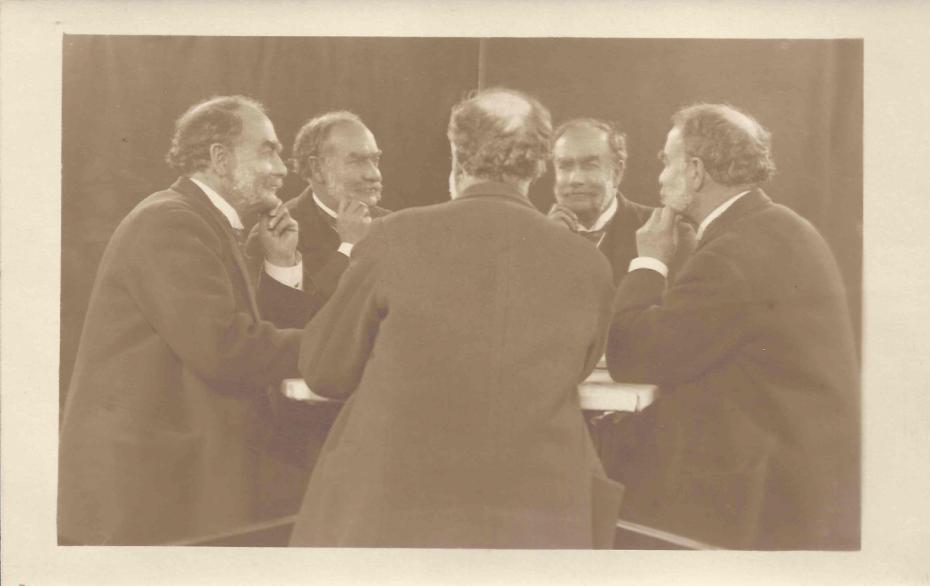

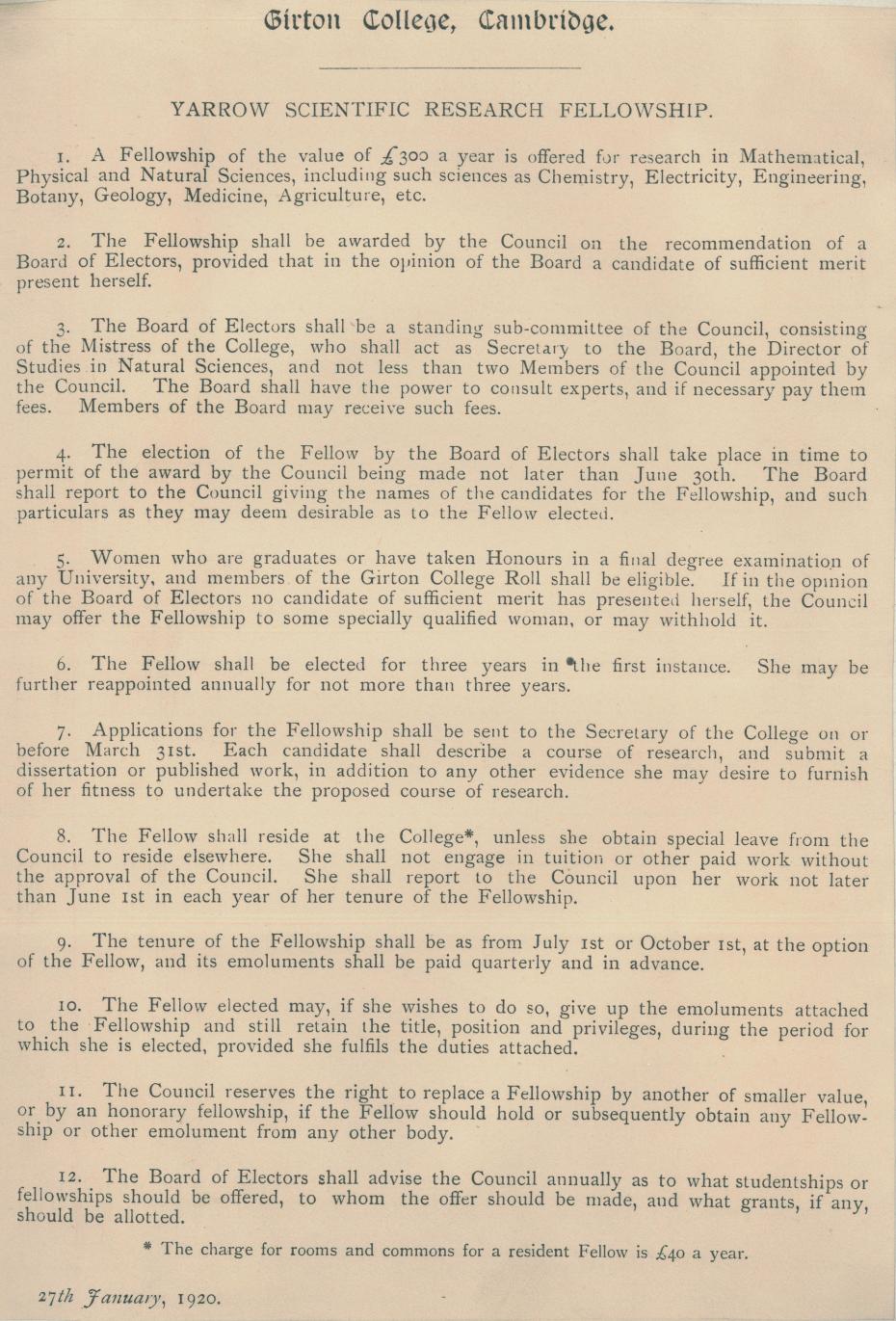

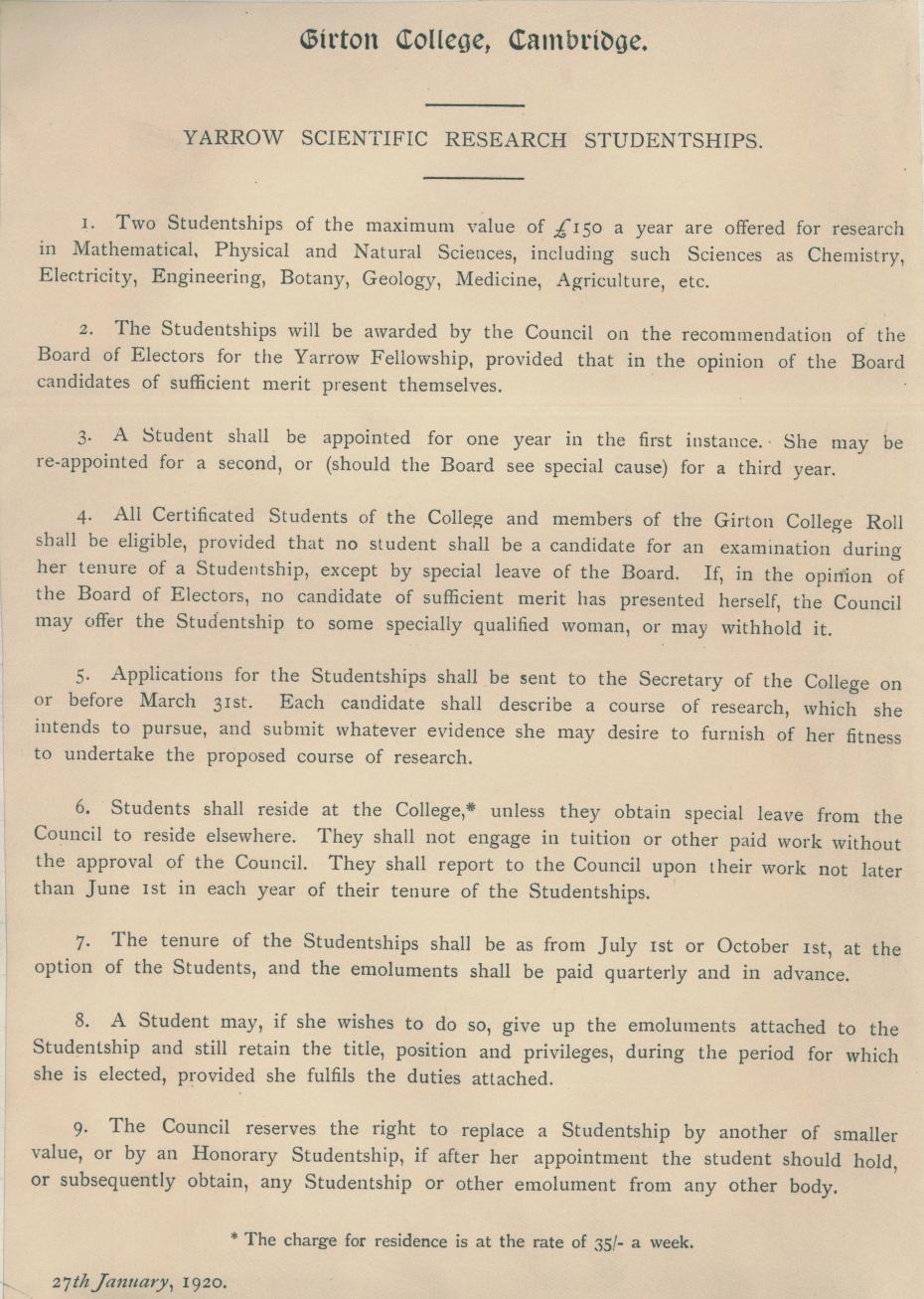

This year’s ceremony profiles Alfred Yarrow who is one of Girton’s major benefactors. He too was a profilic inventor; an engineer who recognised the importance of scientific research by women and men alike.

Second Reading read by Members of the Girton College Chapel Choir

When Great Trees Fall by Maya Angelou (1928-2014)

This poem by acclaimed storyteller, autobiographer and civil rights activist Maya Angelou is about love, loss and renewal. We have chosen it to recognise that for every name read out in this ceremony there are families, perhaps generations of them, that mourn their loss. For some that loss is still very raw: a great tree has fallen in the forest.

Reflection on the Act of Remembrance (The Chaplain)

Recitation of Benefactors

The names of over 170 Founders and Benefactors are read by representatives of the College community: the Alumni, Honorary Fellows, Fellows, MCR, JCR, and staff. This year, the Alumni, Honorary Fellows and wider Cambridge community were represented by Professor Dame Madeleine Atkins, President of Lucy Cavendish College, the Life Fellows by former Mistress, Professor Dame Marilyn Strathern, the Fellows by the Vice Mistress Karen Lee, the Research Fellows by Dr. Emma Brownlee, the bye-Fellows by the Revd Dr Tim Boniface, College and Chapel music by Dr. Martin Ennis and Gareth Wilson, the students by the MCR President George Cowperthwaite, and the Staff by the Bursar, Jimmy Anderson.

Reflective Silence

The Choir: O Lord, Hear My Prayer by Moses Hogan (1957-2003)

Final Word (The Mistress)

Organ Voluntary: The Fugue (sostenuto e legato) from Mendelssohn’s Sonata VI in D minor (Op 65, 1845). Played by Organ Scholar Emily Nott