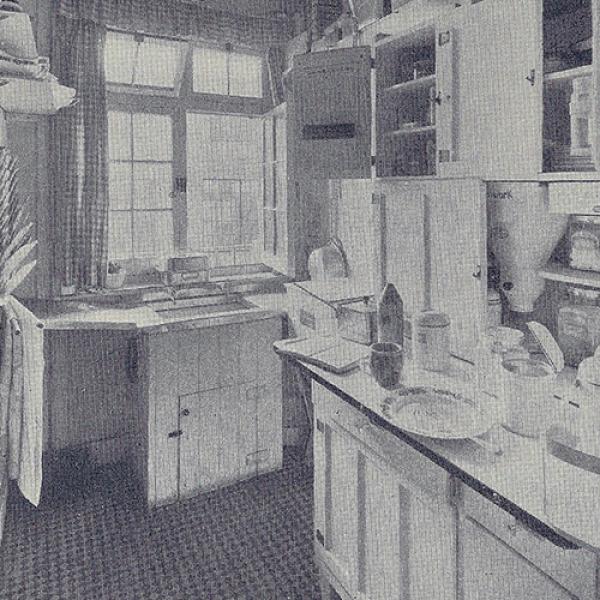

Above: A surviving Easiwork kitchen cabinet

Domestic decluttering influencers are nothing new. TV historian Professor Deborah Sugg Ryan reveals how nearly a century ago a trailblazing Girtonian was giving similar advice to modern housewives in print and on the radio

In the really modern kitchen, where the method of a place for everything and everything in its place is followed, and where space is of the utmost importance, there is nothing to compare with the kitchen cabinet for convenience. It is true that the compact cabinet is the greatest stepsaver yet invented. It really brings the latest ideas in good grouping which have become universal in well run offices within the reach of the housewife. Easier Housework by Better Equipment (Country Life, 1929).

These words by Girton graduate, domestic advice writer, lecturer and broadcaster Nancie Clifton Reynolds (1903–1931) were accompanied by a photo of a ‘kitchen cabinet’. It is a free-standing wooden cupboard with multiple doors and drawers: to all intents and purposes it is a kitchen in a cupboard.

The three storeys of open doors of the kitchen cabinet reveal compartments for the storage of food and equipment associated with food preparation. They incorporate a flour sifter shaped like a funnel; flour bin; metal-lined bread drawer; rolling pin; bin for sugar; and storage jars. There is a sliding or fold-down enamelled worktop for food preparation with more cupboards underneath, including a meat safe, and drawers. The inside of the topmost doors often had a ‘shopping or household wants reminder’ – a list of products with a tab next to each item that can be flipped as a reminder to purchase it.

Easiwork was the first company to sell kitchen cabinets in Britain. It was founded in 1919 by the Canadian G.E.W. Crowe who originally imported refrigerators and kitchen cabinets from Canada to Britain. These cabinets were a version of the American Hoosier cabinet, which was first manufactured in Indiana in the late 1890s. The Hoosier cabinet was inspired by the ideas of the Beecher sisters who advised women, in The American Woman’s Home; or Principles of Domestic Science (1869), to incorporate a ‘cooking form’ cabinet in their homes as a rational and hygienic solution to food preparation and storage needs. Production peaked in the 1920s when more than one in ten American households owned a Hoosier brand cabinet. It was championed by economist Christine Fredrick who drew on the methods of efficiency experts and time and motion studies and applied them to the home, installing a Hoosier in her own kitchen.

The Hoosier cabinet was influenced by the nineteenthcentury fall-front secretary desk, patented in 1874 by the Wooton Desk Company of Indianapolis. In the original Wooton desk, hidden behind two massive hinged panels available in a variety of decorative finishes, were 110 letterboxes and cubbyholes to contain the businessman’s important papers and tools of correspondence, all of which could be reached from a seated position. When the working day was through, the sides of the desk could swing shut, and be locked securely to ensure privacy and also free up floor space. Wooton’s unique desk not only maintained order in the workplace but was also used by women in the home to keep household papers.

Easiwork produced their own models of kitchen cabinet in Britain from 1922, opening a factory in Shepherd’s Bush, and a showroom in Tottenham Court Road, London. Their early models were quite expensive, and they aimed them at architect-designed houses. They created a wider market for their kitchen cabinets through advertising directly to servantless housewives in magazines like Ideal Home. One advertisement depicted a housewife working at her kitchen cabinet as if she were a secretary in an office. The Easiwork cabinet was also given credibility through its endorsement by the Good Housekeeping Institute, run by the magazine of the same name, and was featured frequently in the Ideal Home Exhibition. By the mid 1920s most British furniture retailers sold at least one style of kitchen cabinet and they were produced in a range of sizes, prices and specifications by several manufacturers, including Liverpool Hygena Cabinets Ltd who catered to more modest budgets and homes.

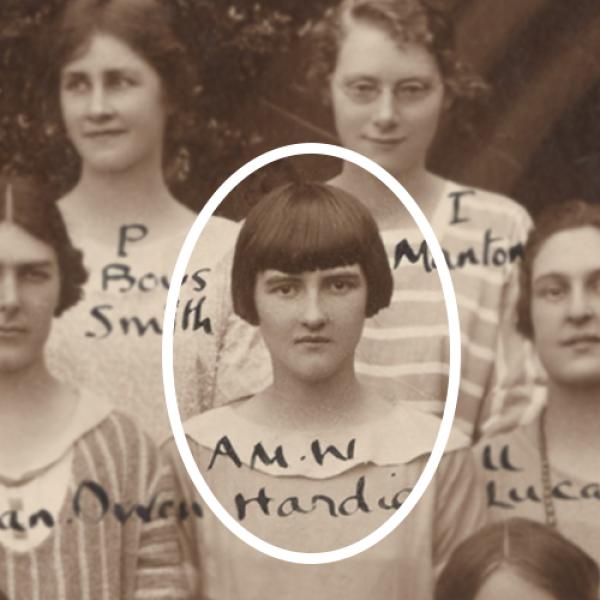

Nancie Clifton Reynolds was a great champion of the kitchen cabinet, educating women in its use through her books, articles, demonstrations and radio broadcasts. Born Agnes Margaret Warden Hardie in Hampstead in 1903, she came up to Girton in 1923, and read two years of Economics and a year of History.

She met the businessman Clifton George Reynolds while she was a student and became his second wife (of three) in 1926, subsequently publishing as Mrs N. Clifton Reynolds. After graduating she worked with him at a factory in Merton, Surrey, manufacturing aluminium products, including cooking utensils. Thereafter they opened a short-lived shop in Streatham called ‘Better Housekeeping’.

Nancie became an expert on using scientific principles of household management, addressing servantless housewives. A reporter commented, ‘She is a most interesting woman, and not only has she been educated in economics, and their various uses in life to-day, but she is backed by very practical experience, being a wife, and mother herself’ (Daily Mail, 15 April 1929). She made eight BBC radio broadcasts on domestic science, known as ‘Household Talks’, between 1927 and 1930. The Radio Times noted that Reynolds’ own home was ‘equipped with every modern convenience and laboursaving device’ (Radio Times, 2 September 1927).